Week 10

Yazan Al-Thibeh

Marikana: Voices from South Africa’s Mining Massacre

Week ten examines Peter Alexader’s and his co-writers book “Marikana: Voices from South Africas Mining Massacre”, where it talks about the Marikana Massacre of August 16, 2012. The Massacre was the single most deadly use of force by South Africa forces against civilians. Those who were killed were mineworkers who demanded better working conditions and support of pay. The book interviews and documents those who survived the attack, where the book meticulously mentions the massacre in great detail. The book did a great job in documenting the events leading up to the massacre of the mineworkers and speaking to family members and who were harassed by the South African police. This book reminded me of the 1990 Oka crisis in Canada, on how there was a land despite with the Mohawk people and Canadian authorities. In the Oka crisis a Canadian officer shot and killed a protester.

Chapter 1: Encounters in Marikana

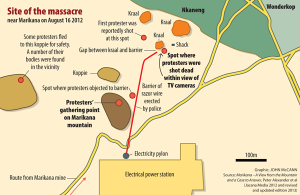

The first chapter gives the reader a background understanding of the events that unraveled in Marikana. Where a couple of weeks before the August 16 2012 massacre, many of the workers decided to strike due to horrible working condions and bad pay. They were receiving $400 (USD) and they were asking for $1000 (USD) (Pg 22). About 3000 workers stopped working to strike having to fail on setting a meeting with Lonmin. The workers were protesting peacefully for unfair working conditions and pay. Some of the workers were carrying knobkerries, sticks and whips to protect themselves from authorities. Within days of the protest 9 people were killed and many more were injured, the tension between both sides escalated. On August 16th 2012, the South African authorities were responsible for injuring 78 people and killing 34. That day was really significant in post-apartheid Africa since it was the day the police used force against civilians.

Chapter 2: A Narrative Account Based on Workers’ Testimonies

The second chapter talks about the struggles that the worker were dealing with and the lack of human rights. The works were threatened by authorities if they did not go back to work when they were protesting. The officers would scare the workers by physically harming them and by touching their homes. On the day of the massacre news stations gathered to take note what happened. The news crated a narrative on how bad and ruthless the workers were, in reality they were the ones that were being oppressed. The workers were trying to build a better future for themselves and family and yet they were seen as the villains. The workers just demanded their employer, Lonmin, to listen to their case for a decent wage. This part of the book reminded me of the article “India in Africa: changing geographies of power”, on how some of the African workers were treated when they were working on the oil-rig, and how some were treated like animals.

Chapter 5: Interviews with Mineworkers

The fifth chapter, looks at the issues and events before and after the massacre. I liked this chapter the most because it entailed unedited literature and interviews from the works and their families. The chapter gives descriptive notes on the emotions towards the massacre and the mine. This chapter allowed the reader to understand the actors involved, (mine company, African National Congress, religious leaders, mine workers, and the National Union of Mineworkers), and come up with a conclusion and opinion on who is to blame.

Discussion

What other cases, in Canada or around the world, were similar to this one?

Were you surprised that South African authorities were threatening and harassing the works?

Why the interviews from the mine works are was crucial in writing this book?

How much of an impact did the media have in influencing this issue, and how might social media today change the way we view events like these?

Why is it really important to study the agents in this case?