Jessica Slade- 110232060

For the purposes of this week’s blog post, I will be responding to the work of Peter Alexander, Thapelo Lekgowa, Botsang Mmope, Luke Sinwell, and Bongani Xezwi in the book, “Marikana: Voices from South Africa’s Mining Massacre.” This work was published in 2013 and provides reliable insight into the massacre that took the lives of many mine workers on strike in August of 2012. By providing insight into the thoughts and feelings of those directly involved, we are exposed to the raw and real accounts as presented by the interviews and testimonies.

In the beginning we read, “Chapter 1: Encounters in Marikana” which provided us with background information on the preceding events that lead up to the tragedy in Marikana. After numerous attempts to set a meeting with Lonmin, approx. 3000 workers walked off the job and began the strike. The workers were protesting poor condition and unfair wages, in a manner described as relatively peaceful in protests. Initially armed with sticks, machetes and spheres, their physical threat against authorities was minimal. In the coming days, 9 people were killed and this furthered the tensions on both sides. On August 16th, the South African Police Service was responsible for the deaths of 34 people and injuring 78 more. This event was significant as it was one of the greatest uses of force used against civilians, in post-apartheid Africa. Why are the encounters described in this chapter crucial to the events that lead up to the Marikana massacre? Were you surprised as to the rapid increase of violent events that occurred just days after the initial protest?

The next chapter required from this work was, “Chapter 2: A Narrative Account Based on Workers’ Testimonies”. Here we learn of the struggles associated with this line of work and the minimal rights that the miners were entitled to. In the days following the protests workers were warned that if they did not return to work they would be immediately dismissed from the company. Additionally there were threats regarding the ‘torching’ of their homes and physical threats of harm. The shooting was a controversial topic covered by many news sources and this chapter accounts for this in an investigative manner, examining the events in great detail. By compiling and comparing the roles of each actor (the African National Congress, the mine company and the National Union of Mineworkers), we can see the media was responsible for alienating the protesters by means of creating a narrative where they were ruthless savages- when in reality they were striking with hopes for a brighter future for their families. Why is recognizing the role of each actor important in establishing a full and clear picture of how the events played out? What was the role of each and how did they further support or refute the cause? How did the media play an important role in this cause; did it work to hinder the campaign or make it stronger?

“Chapter 5: Interviews with Mineworkers”, presents us with first hand and conclusive sense of what the leading events and after affects of the massacre. The unedited accounts provide the reader and literature with a sense of real justifications where workers emotions and feelings towards events are concerned. Gaining insight into the shooting and the events that preceded and followed it, we are able to conclude in creating a larger more in depth understanding of the roles of each actors and the opinions of each. Some of the most important that are touched on throughout the duration of this work are as follows: the government, opposition parties and politicians outside the government, trade unions, mine owners, strikers families, religious leaders, media, and the international community.

In doing further research into the legal implications of this event it is interesting to see that the of the miners arrested, 270 were charged with public violence- which was then later redefined as murder, regardless of the fact that the opposing forces shot at them. Here it is relevant to consider the biases present and how this has played out in the judicial system. Why is this relevant to the events that occurred? How is this a display of intentional bias in sentencing? Is systematic oppression a construction here; how does the narrative counter this or perpetuate it (consider the place of the union)? Where have we seen this occur before and what has the public opinion been on this type of action? Is this similar or different to the publics view on the charges seen in this case? By providing an emotional and personal insight into the events, the authors conclusively presented the events in a way that we are able to empathize with all those affected.

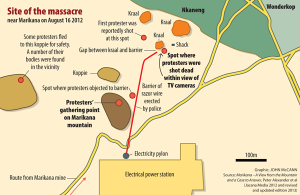

This image is interesting as it physically maps out each of the important sections of the events. In looking at this we are able to gain a more conclusive and insightful understanding as to the proximity of each occurrence.

For a more current account, read the work published by Time Magazine in August of 2013: http://world.time.com/2013/08/16/south-africas-marikana-massacre-a-year-later-workers-and-unions-still-up-in-arms/ . This article takes a comprehensive look at how the events have continued to unfold and how worker and union relations are still strained.