In the introduction of Oxford Street, Accra by Ato Quayson, he distinguishes two questions that repeatedly come to light throughout his text. The first addresses how to appropriately narrate urban space in an African city where space is determined by contradictory spatial logics and the second focuses on how global capitalism produces urban universalism while producing a split from the recognition of the disparities brought with this mode of universalism (32). Focusing on these topics, Quayson provides an in-depth narrative that is integral for understanding Accra’s cultural, economic and global transformation.

In chapter 4, “The Beautyful Ones”, Quayson deciphers slogans on the back of tro-tros and billboards that line Oxford Street, particularly focusing on the cosmopolitan and transnational tone many portrayed. One of the most interesting billboard campaigns critiqued was by TIGO, during the height of the soccer World Cup in Germany, of which Ghana qualified. These billboards depicted images of cosmopolitanism through the light hue of the model’s skin, suggesting mixed-race origins and the popular brands of their clothes, marked distinctly from other billboards on the street that displayed darker toned females with no-name brand outfits (146-148). Why do these disparities exist to this extent and is the future of entextualization on Oxford Street solely cosmopolitan or will nationalism still persist?

Chapter 5, “Este Loco, Loco”, reiterates the theme of transnationalism when discussing with salsa dancers how they were first introduced to the art, articulating a transnational network either personally, through family or from an encounter with a foreigner. This dimension goes further, with the use of the Internet, primarily videos, depicting different dance moves (169). It is interesting to see the impact of globalization on Ghana in this art form. Do individuals who partake in this transnational narrative have the capability of engaging in other art forms that are not derived from their own country? Does this type of cultural behaviour indicate that Ghana is moving towards a state of cosmopolitanism? If so, how does this compare to Canada’s relation to the concept? Is Ghana accepting cosmopolitan notions faster than Canada? Consider Canada’s recurring push for nationalism through declaring, “We are not the USA” from various campaigns and companies (ex. Tim Horton’s).

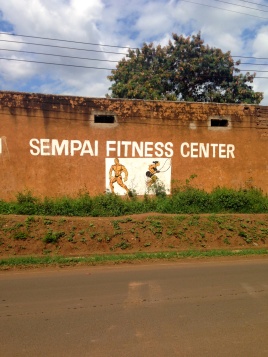

In chapter 6, Pumping Irony, Quayson compares the male individuals, “gymmers”, who frequently partake in gym exercises and weight-lifting competitions to the salsa dancers in the previous chapter, identifying their differences, the main being that the middle class population and their transnational cohorts dominate the salsa scene, where as gymming is largely conquered by the unemployed (185).

Supplemental information:

Here is a picture I captured when I walking one day in Moshi, Tanzania and took a different route home. The image of the male individual advertised on the outside of this gym is parallel to what Quayson was discussing with how males aim to look strong and fit for prospective career purposes.